Historians pursue “big” questions. What makes a civilization? What forces drive them to rise, expand, conquer, but then contrive to drag them into decline? What motivates us, directs our actions, creates the belonging we feel to the communities we construct around ourselves? The field was not always oriented toward finding these deeper truths. Herodotus (484-425 BCE) sought to chronicle the societies of the Mediterranean, North Africa and Western Asia in The Histories, and is rightfully considered the “Father of History,” but presenting an accurate retelling of the past is only part of the venture of history as it is practiced now.

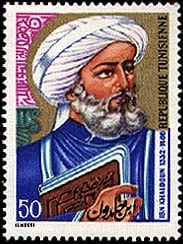

Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406 CE) was the first scholar to study history analytically. He tried to explain the progression of civilizations over time as a function of social, cultural, and economic forces that existed above and outside any one individual. Born into a well-respected family in Tunis, Khaldun was raised and educated in the courts of the Hafsid sultans of Tunisia, eventually becoming a courtier, minister, and diplomat in the service of princes throughout North Africa. Around 1375, tired of the endlessly shifting politics of court life, he sought refuge with the Berber tribesmen of western Algeria to focus on his masterwork: the Kitab al-Ibar, or Book of Lessons.

The Kitab al-Ibar attempts to be a comprehensive history of mankind split into seven massive volumes, and in the first volume, the Muqaddimah, Khaldun establishes methodology that historians, sociologists, and economists would recognize today. The Muqaddimah puts forth Khaldun's model for how civilizations evolve through social conflict and generational evolution. The key social conflict was between nomadic and sedentary lifestyles. The first generation of a new state “retains its nomadic roughness and savagery, and such nomadic characteristics as a hard life, courage, predatoriness, and the desire to share glory.”(117)* The hardship of living as nomads not only steels the new state's citizens, making them superlative warriors, their shared experience of scarcity and struggle also gives them a sense of unity and identity, or asabiyyah.

By the second generation, these values begin to fade, since they,

…have already passed from the nomadic to the sedentary way of life, owing to the power they wield and the luxury they enjoy. They have abandoned their rough life for an easy and luxurious one. Instead of all sharing in the power and glory of the state, one wields it alone, the rest being too indolent to claim their part. (117)

The new, settled way of living replaces aggressiveness with contentment, ardent solidarity with submissiveness and deference. Little to no tradition of greatness remains by the third generation “for they never enjoyed independent action, but were always dependent on the rulers... [O]nce, therefore, the trunk has been removed, the branches cannot strike roots for themselves, but wither and pass away.” (120)

This narrative—a strong nomadic people united by adversity growing into a bureaucratic, lethargic state—undoubtedly has its limitations. For one, the way Khaldun uses “civilization” is broad and could apply to virtually any large collection of human beings. His theory also implies that the progression from nomadic to sedentary is inevitable. Yet, a people may remain nomadic, like the Tuareg of northern and Saharan Africa, and sedentary peoples can retain “predatoriness” across centuries of conquest. Settled societies often defeated or outlived the “rough” peoples at their borders—Republican and Imperial Rome were nothing if not fervently martial and “aggressive.”

These criticisms aside, ibn Khaldun's contribution in the Muqaddimah is invaluable. Rather than merely recounting past events, or rendering them into neatly packaged moral parables, Khaldun was applying a theoretical framework to these events to simultaneously reveal and explain the forces that motivated them. He was pioneering a scientific approach to studying the world by relying on direct study and observation, objectivism, and critical evaluation of evidence.

This perspective made it possible to consider the idea that the functioning of a state was not dependent on the whims of a great leader, or the supernatural influence of fickle deities; more abstract, subtle, often more powerful forces were at work. In Khaldun's interpretation, the rough lifestyle of a nomadic Berber or the market pressures felt by an urban merchant were as essential to understanding history as the great victories of a general or the political wiles of a grand vizier. This made possible the currents fields of political science, economics, sociology, historiography, and it broadened and deepened the study of history. Ibn Khaldun pushed us to think beyond “What happened?” to start asking “And why that way?”

*All quotations are taken from An Arab Philosophy of History: Selections from the Prolegomena of Ibn Khaldun of Tunis (1332-1406), translated by Charles Issawi, 1987. Thanks to Dr. Stacy Fahrenthold (Williams College) for providing me with a copy.

Bibliography:

Hozien, Muhammad. "IBN KHALDUN - His Life and Work." IBN KHALDUN - His Life and Work. www.muslimphilosophy.com/ik/klf.htm. Accessed April 2, 2015.

Ibn Khaldun, and Franz Rosenthal. The Muqaddimah : An Introduction to History. 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1967.

Issawi, Charles Philip. An Arab Philosophy of History: Selections from the Prolegomena of Ibn Khaldun of Tunis (1332-1406). Princeton, NJ, USA: Darwin Press, 1987.

Shadeed, Khalil. “Scholar's Chair interview: Dr. Charles E. Butterworth - Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddimah.” Video. www.youtube.com/watch?v=VWyYoW_ZfY0. Pubished October 28, 2012. Accessed March 31, 2015.

Full text of the Muqaddimah. http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ik/Muqaddimah/.